Insulin Resistance Starts in Your Gut—Why Your Glucose Meter Isn’t Telling the Full Story

A 47-year-old executive came to my clinic frustrated. Despite cutting sugar, tracking macros, and exercising six days a week, her fasting glucose crept from 92 to 98 mg/dL over two years. Her physician reassured her she was “fine—not even pre-diabetic yet.”

The problem? She wasn’t fine. Microbiome analysis revealed severely depleted butyrate-producing bacteria and an overgrowth of pro-inflammatory taxa. Her insulin resistance had been developing silently for years—we were just looking in the wrong place.

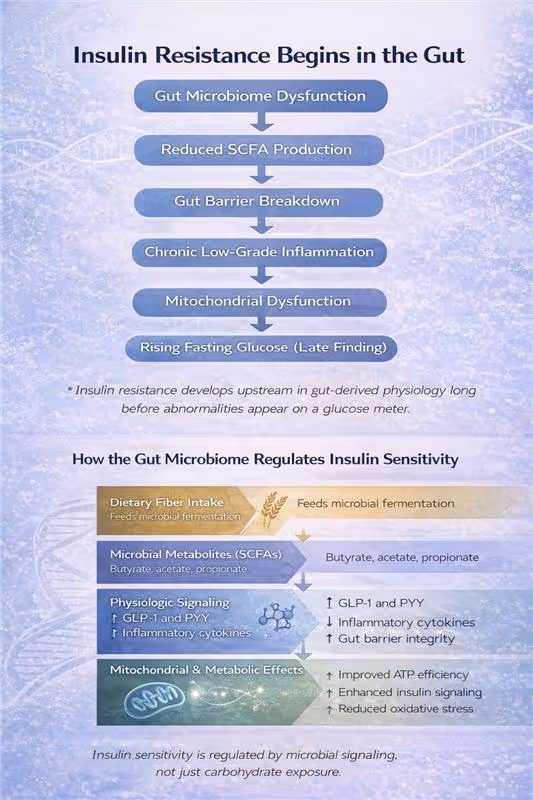

By the time fasting glucose values become abnormal, it’s often too late to catch early dysfunction. Research increasingly shows that insulin resistance begins in the gut, often a decade before traditional blood sugar tests detects it. Understanding this early microbial contribution is key to preventing and reversing metabolic dysfunction.

Executive Summary

- Insulin resistance begins in the gut, often years before glucose becomes abnormal

- Microbial diversity and butyrate-producing bacteria are central to insulin sensitivity

- Short-chain fatty acids act as metabolic regulators, not just digestive byproducts

- Cutting sugar without supporting gut health misses the underlying mechanism

- Early detection through microbiome and insulin assessment enables preventive intervention

- Metabolic resilience—not just lower glucose—should be the goal

Why Your Glucose Meter Tells an Incomplete Story

Insulin sensitivity reflects how efficiently your tissues—muscle, liver, and fat—respond to insulin's signal to take up and use glucose. When sensitivity declines, your pancreas compensates by pumping out more insulin to maintain normal glucose levels.

This means you can have completely normal fasting glucose and HbA1c while your insulin levels are silently climbing—a state called compensatory hyperinsulinemia. This precedes metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes by years, sometimes decades.

Here's what most people miss: This early dysfunction doesn't start with excess sugar intake. It begins with gut-derived inflammation, altered microbial metabolite production, and impaired intestinal barrier integrity. Your gut microbiome is an upstream regulator of metabolic health, not a passive bystander.

The Microbiome Signature of Insulin Resistance

Large-scale microbiome analyses consistently show that metabolic health correlates with two key microbial features:

Higher microbial diversity associates with lower insulin resistance and reduced type 2 diabetes risk. A recent JAMA Network Open study identified specific bacterial families—particularly butyrate-producing taxa like Christensenellaceae and Ruminococcaceae—whose presence predicts metabolic resilience.

Microbial composition shifts precede metabolic disease. Before glucose becomes abnormal, insulin-resistant individuals show:

- Depletion of beneficial bacteria (Akkermansia muciniphila, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Bifidobacterium species)

- Enrichment of proinflammatory taxa (particularly E. coli and related species)

- Reduced capacity for fiber fermentation and SCFA production

This isn't just correlation. These microbial changes drive the inflammatory and metabolic dysfunction that impairs insulin signaling.

How Your Gut Bacteria Control Glucose Metabolism

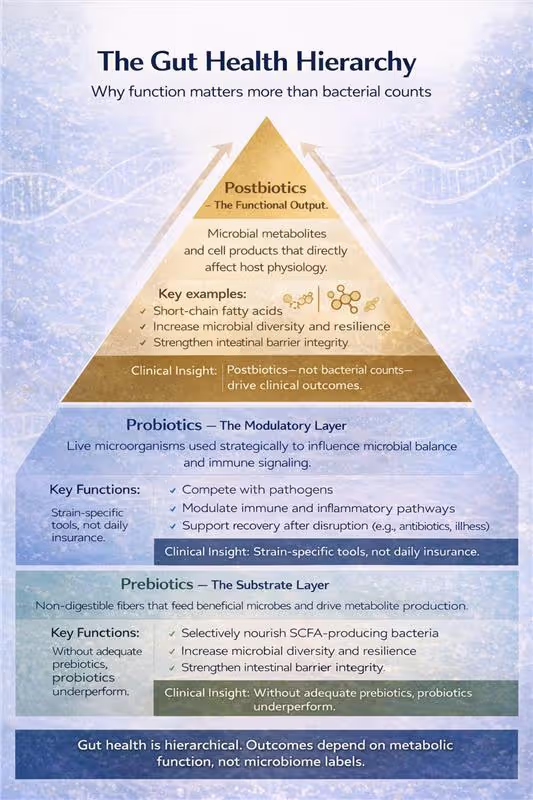

The gut microbiome influences insulin sensitivity through multiple interconnected pathways:

Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production

When beneficial bacteria ferment dietary fiber, they produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)—primarily butyrate, acetate, and propionate. These molecules are metabolic regulators, not just byproducts:

- SCFAs stimulate GLP-1 secretion from intestinal cells, enhancing glucose-dependent insulin release and improving postprandial glucose control

- Butyrate activates AMPK signaling in muscle and liver, directly improving insulin sensitivity and metabolic flexibility

- SCFAs strengthen intestinal barrier integrity, reducing endotoxin translocation that triggers systemic inflammation

This positions fiber-fermenting bacteria as functional regulators of your metabolic state. When these bacteria are depleted, SCFA production drops—and insulin sensitivity follows.

Inflammatory Tone and Barrier Function

A compromised intestinal barrier allows bacterial fragments (lipopolysaccharide/LPS) to enter circulation, triggering chronic low-grade inflammation. This "metabolic endotoxemia" impairs insulin receptor signaling in muscle, liver, and fat tissue—creating insulin resistance independent of caloric intake or body weight.

Carbohydrate Processing Efficiency

Multi-omics studies reveal that insulin-resistant individuals have elevated fecal carbohydrates—particularly host-accessible monosaccharides. This indicates inefficient microbial processing: dietary carbohydrates pass through without being converted to beneficial SCFAs.

In contrast, microbiomes with robust fiber-fermenting capacity efficiently convert dietary carbohydrates into metabolic regulators. This is why carbohydrate quality and microbial function matter more than carbohydrate quantity alone.

Gut-Brain and Bile Acid Pathways

Additional mechanisms include gut-brain neuronal signaling that modulates hypothalamic insulin sensitivity and microbial modification of bile acids that influence glucose homeostasis through receptor-mediated pathways. The gut functions as a metabolic command center, not just a digestive tube.

Why Cutting Sugar Isn't Enough

Reducing sugar intake may improve glucose readings short-term, but it doesn't address the biological drivers of insulin resistance. Worse, excessive carbohydrate restriction often reduces dietary fiber intake—inadvertently depleting the butyrate-producing bacteria that protect metabolic health.

I've seen this repeatedly: patients cut carbs to single digits, lose the initial weight, then plateau with persistent inflammation and poor metabolic flexibility. Their microbiome testing reveals the problem: they eliminated fiber along with sugar, collapsing microbial diversity.

The real objective isn't just lower glucose values—it's metabolic resilience: the capacity to manage glucose efficiently across varying dietary, training, and stress conditions. That resilience is built in the gut.

My Clinical Approach

When patients come to me concerned about insulin resistance or early metabolic dysfunction, I start with comprehensive metabolic assessment—looking beyond standard glucose markers to include insulin levels, inflammatory markers, and microbiome function when indicated.

From there, we develop a targeted protocol that addresses the root causes: optimizing fiber intake and microbial diversity, supporting SCFA production, reducing gut-derived inflammation, and implementing lifestyle factors that enhance insulin sensitivity. The specific interventions are personalized based on your unique metabolic profile and microbiome findings.

This systematic approach catches metabolic dysfunction early—before glucose becomes abnormal and tissue damage accumulates.

The Early Detection Advantage

Here's what excites me about this gut-first approach: we can identify and intervene on insulin resistance years before conventional markers flag a problem.

A microbiome depleted in butyrate-producers with elevated inflammatory taxa tells me insulin resistance is developing—even when fasting glucose is 85 mg/dL. This allows for early, targeted intervention when reversal is most achievable.

Compare this to waiting until fasting glucose hits 100 mg/dL or HbA1c reaches 5.7%—at that point, you've already spent years in a pro-inflammatory, insulin-resistant state causing cumulative tissue damage.

The gut microbiome provides a metabolic early-warning system. We just need to listen to it.

The Longevity Perspective

Insulin sensitivity isn't just about avoiding diabetes—it's a central pillar of healthspan. Insulin resistance accelerates aging biology through multiple mechanisms: chronic inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, advanced glycation end products, and impaired cellular repair processes.

Maintaining insulin sensitivity as you age requires addressing the biological system that regulates it: your gut microbiome. This means supporting microbial diversity, optimizing fiber fermentation, maintaining barrier integrity, and minimizing inflammatory signals from the gut.

When patients ask me about longevity interventions, metabolic health through microbiome optimization consistently ranks at the top. It's foundational, modifiable, and has cascading benefits across every physiological system.

Dr. Banerjee is a board-certified gastroenterologist with over 15 years of clinical experience, peer-reviewed publications indexed in PubMed, and deep expertise in gut microbiome science. He advises high-achieving individuals and families on precision longevity and healthspan optimization. Expanded clinical analysis is available through the Private Longevity Briefing.

Peer-Reviewed Clinical and Mechanistic Research

- Canfora EE, Meex RCR, Venema K, Blaak EE. Gut microbial metabolites in obesity, NAFLD and T2DM. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(5):261-273. doi:10.1038/s41574-019-0156-z

- Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56(7):1761-1772. doi:10.2337/db06-1491

- Camilleri M. Leaky gut: mechanisms, measurement and clinical implications in humans. Gut. 2019;68(8):1516-1526. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318427

- Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444(7121):860-867. doi:10.1038/nature05485

- Imdad S, Lim W, Kim JH, Kang C. Intertwined Relationship of Mitochondrial Metabolism, Gut Microbiome and Exercise Potential. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5):2679. Published 2022 Feb 28. doi:10.3390/ijms23052679

.svg)